Identifying Restoration in Contemporary Prints

In my capacity as a former art dealer and gallerist, I have engaged in transactions involving originals, works on paper and prints by many of the leading contemporary artists of our time. Spanning a career of over three decades, works by Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Roy Lichtenstein and others have been presented to me for sale. With regard to limited edition prints, this vantage point has afforded me the opportunity to examine multiple impressions from various editions over an extended period of time. On select occasions, I have seen two or more impressions of a particular edition side by side. This rarity facilitated the ability to conduct a thorough comparative analysis . Additionally, for a portion of my career, I also had a first hand-look into the restoration processes applied to numerous contemporary prints.

Let’s begin by establishing definitions. In the realm of fine art, you may see terminology that a work has been conserved or restored. Here are the definitions from the American Institute for Conservation to clarify each, in the context of art:

Conservation

The profession is devoted to the preservation of cultural property for the future. Conservation activities include examination, documentation, treatment, and preventive care, supported by research and education.

Restoration

Treatment procedures intended to return cultural property to a known or assumed state, often through the addition of non-original material

(Source: https://www.culturalheritage.org/about-conservation/what-is-conservation/definitions)

When it’s stated a work of art has undergone conservation or restoration, for some, these terms are perceived interchangeably, signifying the work has been repaired in some manner in an effort to improve the work or to reinstate it to its original condition. Conversely, for others, the former concerns halting further degradation of the work, while the latter implies an endeavor to return the work to its initial condition. In the context of this article, I will utilize the term restoration, as much of the discussion pertains to the process of returning a print to its ostensibly original state.

The practice of restoration with fine art is little discussed and often remains undisclosed, creating a blind spot for collectors. So, how do we know what to look for in terms of restoration with contemporary prints?

Cockling

Certain types of restoration are minor and have little effect on the value of a work of art. For example, cockling, which is a planar distortion of the paper, can appear as wrinkles, half circles, ripples, or puckers, usually a result of moisture exposure or if there is insufficient space within a frame for the paper to expand and contract. Remediation of mild cockling with a vacuum press typically improves the print’s appearance and does not affect value. However, severe cockling can be challenging to address due to the paper’s memory, which may lead to a recurrence of the distortion even after a vacuum press treatment.

Creases

Creases, often incurred by mishandling, are typically amenable to manual pressing. When minor in nature and skillfully addressed, creases do not have a detrimental effect on the artwork’s value.

Example of a handling crease. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Tears

Tears present a more substantial concern and are frequently mitigated through adhesive methods to reduce their visibility. The repair of a tear is generally more feasible and less detrimental to the artwork when it occurs within the white paper border of a print as opposed to being within the image itself.

Example of tears at the bottom of a Warhol Candy Box Heart. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Staining

Staining, whether caused by moisture or from acidity, holds varying degrees of significance depending on the extent of damage inflicted upon the print. Water damage typically results from direct exposure, while foxing, which presents as rust, black or yellowish spots, can arise from humidity, fungal growth or oxidation. “Mat burn” occurs over time when acidity from paper matting interacts with the paper of the work. When these issues are not severe, they can often be addressed through various cleaning methods. However, if any of these issues exist in a severe form, remediation may prove challenging or impossible, thereby significantly diminishing the value of the print.

Light Strike

Prints can also experience what is termed “light strike”, which indicates that a piece of art has toned or attenuated from exposure to ultraviolet light. This exposure can result in the fading of certain inks and pigments, as well as the darkening of the paper substrate. Different colors exhibit varying degrees of susceptibility to fading, with red, orange, and neon hues often displaying more noticeable fading in comparison to colors like blue or black. Below is an illustration featuring a Roy Lichtenstein Sunrise that has suffered light strike:

Roy Lichtenstein, Sunrise, 1965, Offset lithograph, image: 17 5/16 x 23 1/4, sheet: 18 5/16 x 24 5/16. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Airbrushed

This issue of color attenuation leads us to the topic of airbrushing. In discussing an airbrushed print, some say, “This print has been re-screened”, but this is a misnomer. Airbrushed prints have not been re-screened, they’ve been airbrushed.

When a print possesses significant value, its market price tends to be lower if it appears faded or light struck than if it appears to be in its original condition. Thus, there is a significant motivation to remedy this through the use of airbrushing, which, akin to inpainting, is a method to conceal imperfections. However, airbrushing distinguishes itself by being a tool-based technique as opposed to a manual one.

Inpainting, conversely, is typically done to conceal smaller areas of restoration, whereas airbrushing is typically employed to conceal more extensive areas. Beyond restoring color to an artwork, airbrushing can also serve to mask evidence of prior creases, tears, and the patching and sanding of the paper substrate.

Case Studies: Prints by Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, and Roy Lichtenstein

Let’s begin with an example by Andy Warhol. The Liz below is an offset lithograph from 1964, signed and dated “Andy Warhol 66”:

Andy Warhol, Liz, offset lithograph on paper, 23 1/8 x 22 1/8”, approximately 300 signed and dated in ball-point pen. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

How can we ascertain this work is in its untreated state, i.e. that it has never been restored or airbrushed? The determination is based on the observation that the red pigment has significantly faded, and is now an almost pinkish hue. Additionally, there is evidence of acid burn in the margin.

Here is the same impression of Liz with the background airbrushed and the margin cleaned. Note the intensity of the red color, which would be highly unusual for a fifty-nine-year-old offset lithograph:

After airbrushing and margin cleaned. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Often, a work may not exhibit as pronounced fading as the example presented above. Here are three impressions of Warhol’s 1964 Liz depicted below. The two on the left have been airbrushed, and the one on the right is in its original state.

Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Below is a close-up of the two unframed artworks. The face and the background of the one on the left has been airbrushed, as indicated by the deeper blue-red ground and the altered pink complexion of the subject’s face. The Liz on the right has not been subjected to airbrushing.

Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Airbrushing can also serve to conceal the presence of creases. Here is an example in Warhol’s The Star where the lower left corner was crushed in transit:

Before paper treatment and airbrushing. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Before paper treatment and airbrushing. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Before paper treatment and airbrushing. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

The corner before treatment. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

The corner after paper treatment and airbrushing. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Keith Haring, Best Buddies, 1991, before and after airbrushing. The figure on the right has been restored to its original color, as well as the purple in the foreground. Observe before and after airbrushing:

Before airbrushing. Keith Haring, Best Buddies, 1991, Screenprint, Image: 22 x 27 5/8”, Sheet: 26 x 32”, Edition of 200. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

After airbrushing. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Recall the previously mentioned light-struck Lichtenstein Sunset. Observe the print before and after undergoing cleaning and airbrushing:

Before cleaning and airbrushing. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

After cleaning and airbrushing. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

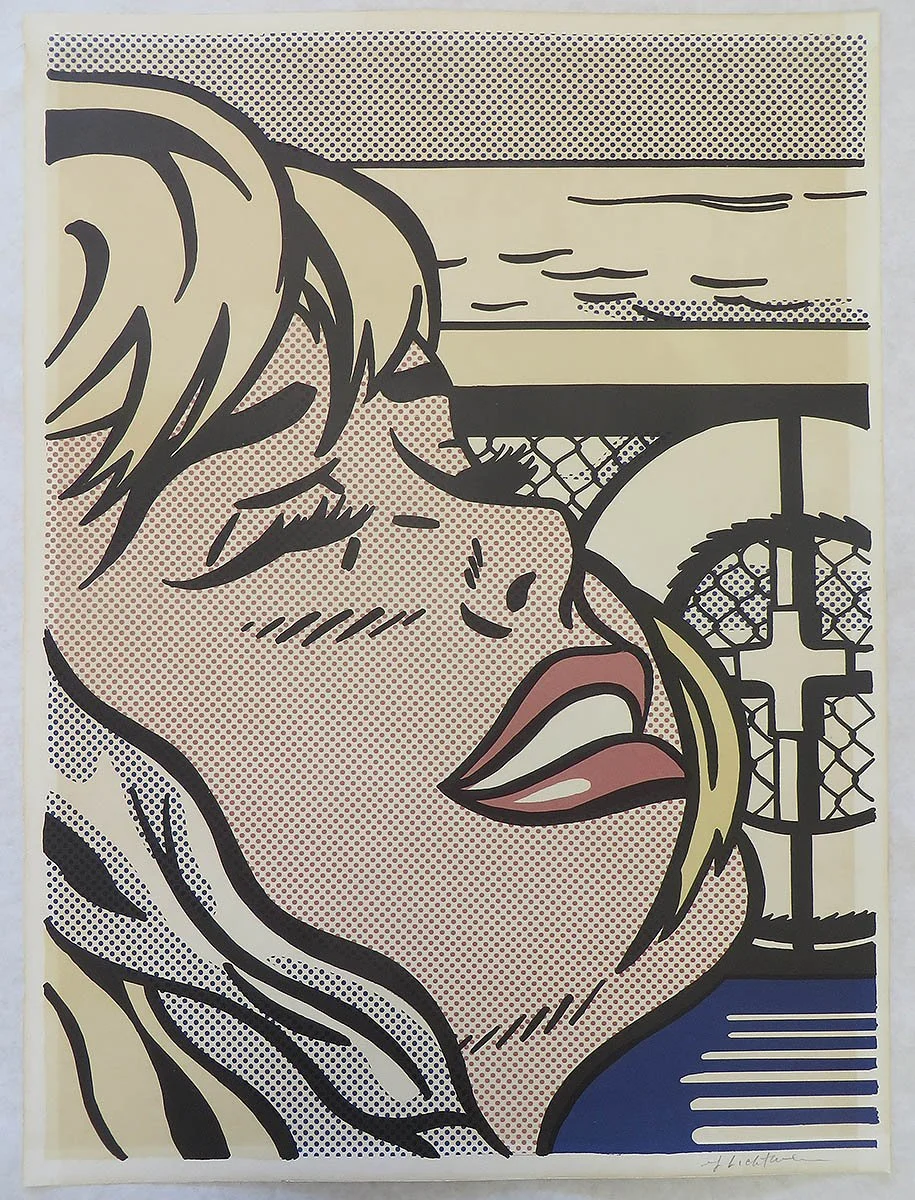

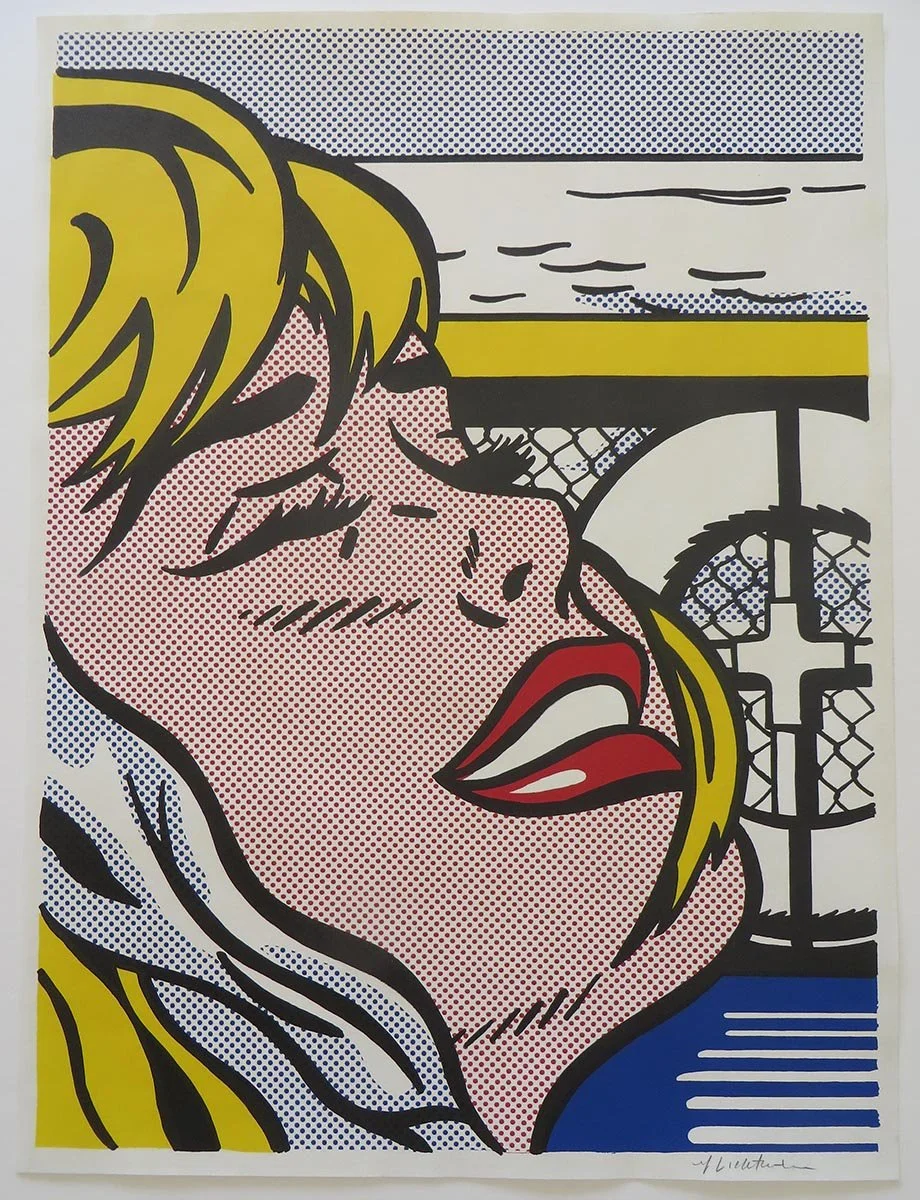

And here is Roy Lichtenstein’s Shipboard Girl before and after airbrushing and cleaning:

Before cleaning and airbrushing. Roy Lichtenstein, Shipboard Girl, 1965, offset lithograph on white wove paper, Image: 26 1/16 x 19 3/16, Sheet: 27 3/16 x 20 1/4 inches. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

After cleaning and airbrushing. Image courtesy of and copyright Dina Brown.

Conclusion

When evaluating a contemporary print for signs of airbrushing, it’s advisable to utilize the catalogue raisonné, if available, as a starting point. While an image in a book can be drastically different from the artwork, it still is a good place to begin. Google Images is very helpful for comparing multiple impressions of the same artwork, as many popular prints have sold at auction houses and other online platforms over time.

While there are exceptional instances of prints maintaining their original vibrancy with minimal toning, such occurrences are rare. Over time, exposure to sunlight, including indirect sunlight, can lead to color fading, with offset lithographs being particularly susceptible in contrast to the more durable pigments found in screenprinting.

UV Plexiglas, available in UF 3, UF 4, or UF 5 grades, offers approximately seven years of optimal UV protection. (UF 3 and 4 filter 95% of UV rays while UF 5 filters out 99%).

Consequently, artworks from the previous century in their original frames likely offer the work of art no protection from harmful ultraviolet rays.

Some instances of airbrushing, as in the case of “The Star”, are challenging to detect without the use of a black light. This tool is usually used in a dark room to reveal any paint fluorescence, which would stand out against the original printed colors. High-end prints, like those by artists like Warhol, Haring, and Lichtenstein, are often examined under black light to verify the absence of airbrushing or inpainting. If one is able to view an unframed work in person, airbrushed areas also will often, though not always, present as a different texture than the inks original to the work.

Limited edition prints by the artists mentioned, above, as well as many other contemporary artists, command prices ranging from $10,000 to nearly $1 million. When in doubt, seek advice from a conservator, appraiser, or reputable dealer to navigate the process effectively.

About the Author:

Dina Brown is the owner of Dina Brown Art Appraisals in Beverly Hills, California. She is a Certified Member of the International Society of Appraisers and is an Accredited Member of the Appraisers Association of America. Visit her website at www.dinabrownartappraisals.com

© Dina Brown 2023